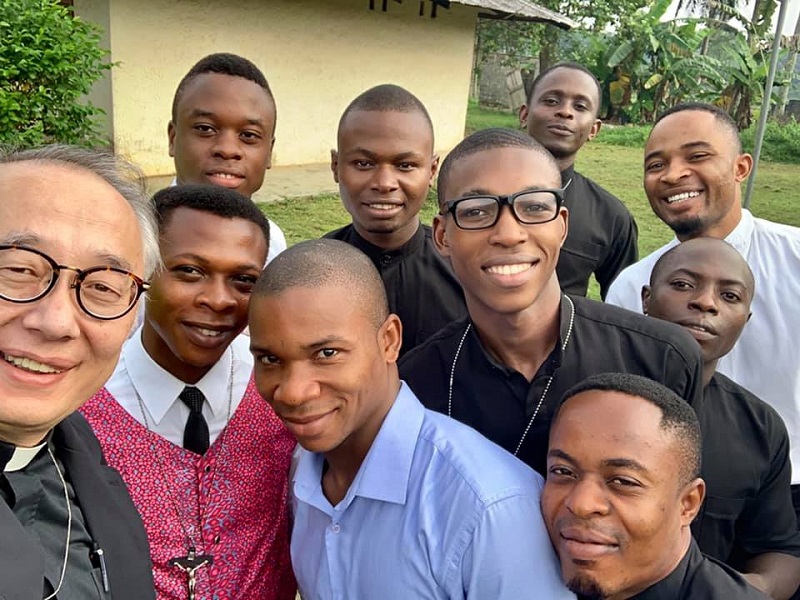

Dr. Masaki is currently overseas in Europe, teaching classes on the theology of the Lutheran Confessions at the Old Latin School in Wittenberg. He is there as a part of the International Lutheran Council’s Lutheran Leadership Development Program, with students ranging from pastors to presidents to bishops and general secretaries, from the Lutheran Churches in Ghana, South Africa, Tanzania, Ethiopia, and Madagascar.

While there, Dr. Masaki also had the chance to attend the first graduation exercises of the STM-Gothenburg program, a joint labor of the Lutheran School of Theology in Gothenburg (FFG, which comes from the Swedish name “Församlingsfakulteten”) and CTSFW. The program takes four years to complete on a part-time basis, allowing the students to both pursue advanced study and continue serving the Church and their congregations as pastors.

“Very proud of our first fruits, Rev. Janne Koskela of the Evangelical Lutheran Mission Diocese of Finland (ELMDF), Romans Kurpnieks of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Latvia (ELCL), and Rev. Hannu Mikkonen of ELMDF,” Dr. Masaki wrote on his Facebook page. “It was a great celebration! A wonderful day! Again, congratulation, Janne, Romans, and Hannu!!”

Bottom row, left to right: Rev. Janne Koskela and Rev. Hannu Mikkonen

(Photo courtesy Rev. Konstantin Subbotin.)

Christopher C. Barnekov, PhD, of the Scandinavian House Fort Wayne (which helps graduate students from Scandinavia study at CTSFW by providing low cost room and board), followed up with an article on the history of the program and the great need–and incredible remnant of confessional Lutherans–in the Nordic and Baltic regions, as well as in Eastern Europe. A slightly shortened version was uploaded to the main CTSFW page, but you can read his full, original article here:

The first three graduates of CTSFW’s STM Extension Program in Gothenburg, Sweden, received their degrees in a special ceremony in Gothenburg on Sunday, February 24. Two pastors from Finland and one from Latvia were the first to complete all the requirements, with several more expected to finish over the next year. The program began in 2014 as a joint effort of CTSFW and the Lutheran School of Theology in Gothenburg (LSTG).

The STM Extension was organized at the request of LSTG to meet an urgent need in the Nordic and Baltic regions for advanced theological training on a confessional Lutheran foundation. The former state churches in the Nordic region have succumbed to liberal theology and reaped empty pews, with average attendance below two percent and the percentage of babies baptized dropping steadily. The STM program largely serves confessional movements, several of which joined the International Lutheran Council last fall. In the Baltic region, the STM Extension serves the Lutheran churches recovering from the devastation wreaked during decades of Soviet occupation.

What was totally unexpected, however, is that many students are also coming from Eastern Europe, from as far as Russia, Ukraine, and Romania. The LCMS Office of International Mission has found this program extremely helpful for their efforts supporting confessional Lutheran churches in this region. So have sister churches such as the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Latvia. As a result, this extension that originally hoped to attract seven or eight students now has about 24 from nine different countries.

The program is offered through three one week “Intensives” per year, normally taught in Gothenburg. Each year CTSFW faculty teach two courses and LSTG faculty teach one. The CTSFW faculty who have taught in Gothenburg thus far include Dr. Naomichi Masaki, the STM Program Director in both Fort Wayne and in Gothenburg, and Professors Rast, Gieschen, Ziegler, and Pless. Dr. Roland Ziegler is teaching a course on Justification this week.

The Gothenburg Extension came about because it was becoming increasingly expensive and increasingly difficult for young pastors to leave their families and their parishes to spend five quarters in Fort Wayne. Yet the need for advanced study was so great that LSTG asked CTSFW to consider an extension. The format of the program, with three one-week sessions per year (and much work before and after the classes), makes it possible for these pastors to attend. With solid support from the CTSFW Administration and Regents, CTSFW has been able to say, “Yes!”

The program is funded by several LCMS congregations and individuals through the “Bo Giertz Fund,” named after the late bishop of Gothenburg best known in America for his novel, The Hammer of God. This fund has so far been able to cover operating costs for both schools, as well as tuition and fees for students from the Nordic and Baltic regions. The LCMS Office of International Mission supports the Eastern European students, and several Nordic foundations help Nordic and Baltic students with travel expenses. A local congregation of the Swedish Mission Province, Immanuel, provides lodging for the students. It is noteworthy that the Pastor of this congregation is The Rev. Jakob Appell and its President is The Rev. Dr. Daniel Johansson … both of whom earned their STM degrees at CTSFW, as have several other leaders of the confessional movement in the Nordic lands.

For information about donating to the Bo Giertz Fund, contact the Advancement Office at [email protected] or by calling (877) 287-4338.

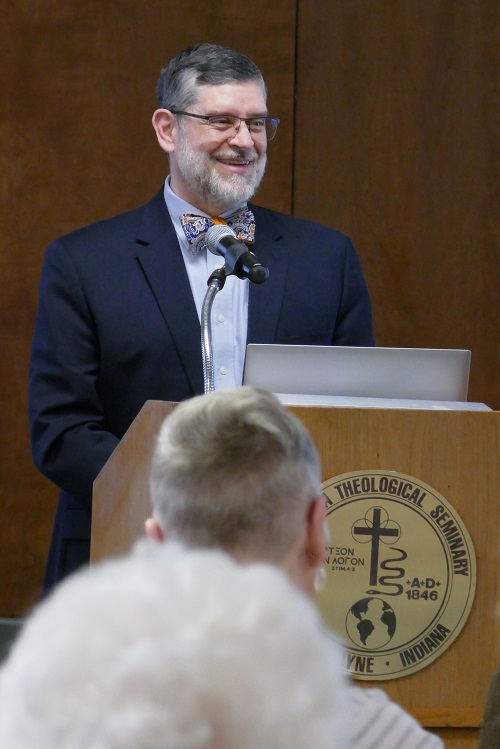

Yesterday at the Seminary Guild’s monthly meeting, Dr. Don Wiley presented on the role and importance of Spanish Language Church Worker Formation in the Church. Dr. Wiley joined the faculty just this past May for this reason (also serving as Assistant Professor of Pastoral Ministry and Missions), though his first introduction to the Spanish language occurred in his own student days at Seminary, when he was unexpectedly given the opportunity for a two-year vicarage to Panama. “God gifted me to learn quickly and well,” he added, noting that the only other language he’d studied before those two years was German while getting a degree in engineering.

Yesterday at the Seminary Guild’s monthly meeting, Dr. Don Wiley presented on the role and importance of Spanish Language Church Worker Formation in the Church. Dr. Wiley joined the faculty just this past May for this reason (also serving as Assistant Professor of Pastoral Ministry and Missions), though his first introduction to the Spanish language occurred in his own student days at Seminary, when he was unexpectedly given the opportunity for a two-year vicarage to Panama. “God gifted me to learn quickly and well,” he added, noting that the only other language he’d studied before those two years was German while getting a degree in engineering. Dr. Wiley also shared some statistics on why Spanish language formation is such an important aspect to ministry: in 2003 Hispanics become the largest minority in the US and in 2018 they made up 18.1% of the population (about 58.1 million people). It is estimated that by 2020 minority children (of all ethnicities) will outnumber the majority, by 2045 minorities overall will outnumber the majority (Dr. Wiley used the term “Anglos” to refer to Caucasians, emphasizing the idea of culture and origin rather than race), and by 2060 nearly a third of the country’s population will be Latino.

Dr. Wiley also shared some statistics on why Spanish language formation is such an important aspect to ministry: in 2003 Hispanics become the largest minority in the US and in 2018 they made up 18.1% of the population (about 58.1 million people). It is estimated that by 2020 minority children (of all ethnicities) will outnumber the majority, by 2045 minorities overall will outnumber the majority (Dr. Wiley used the term “Anglos” to refer to Caucasians, emphasizing the idea of culture and origin rather than race), and by 2060 nearly a third of the country’s population will be Latino.

One of the students with us for two weeks of graduate intensives was Rev. Sorin-Horia Trifa, studying for his Masters in Sacred Theology (STM). Rev. Trifa is the only pastor of The Confessional Lutheran Church in Romania, and an LCMS Alliance Missionary. The Student Mission Society invited him to speak about his home country, for which he has a deep love. “I saw [the Romanian flag] also here,” he said, pointing in the direction of the library, where we keep flags representing all the nations of our current students, “and I am very proud.” About 92,000 square miles with 19.6 million people, Romania is barely 100 years old, the result of the merging of three countries: Transylvania, Walachia, and Moldavia.

One of the students with us for two weeks of graduate intensives was Rev. Sorin-Horia Trifa, studying for his Masters in Sacred Theology (STM). Rev. Trifa is the only pastor of The Confessional Lutheran Church in Romania, and an LCMS Alliance Missionary. The Student Mission Society invited him to speak about his home country, for which he has a deep love. “I saw [the Romanian flag] also here,” he said, pointing in the direction of the library, where we keep flags representing all the nations of our current students, “and I am very proud.” About 92,000 square miles with 19.6 million people, Romania is barely 100 years old, the result of the merging of three countries: Transylvania, Walachia, and Moldavia.