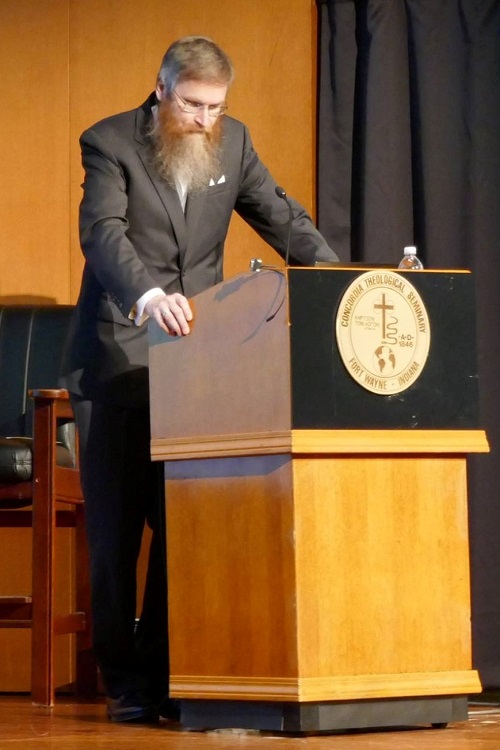

President Rast held a Collegial Conversation today following chapel. The Collegial Conversations are a quarterly convocation for all MDiv, AR, and deaconess students, in which the president speaks on a topic that will affect students after they leave the Seminary. For the opening quarter of this academic year, Dr. Rast presented on leadership and authority, shaping his talk around the verses of LSB 718:

“Jesus, lead Thou on

Till our rest is won.

Heav’nly leader, still direct us,

Still support, console, protect us,

Till we safely stand

In our fatherland.”

Dr. Rast pointed out that, for future deaconesses and pastors, “It’s not ‘will I be a leader’ but ‘what kind of leader will I be.’” His practical advice? “Be intentional about it. Use the style that best fits you and don’t fall into the temptation of falling back on authority.” (Such as, “You must listen to me because I am the pastor/deaconess/etc.”) “As soon as you make that statement,” Dr. Rast declared, “your authority is shot because you’ve gone the way of the law.”

Always the historian (besides his role as President of CTSFW, he also serves as Professor of Historical Theology), Dr. Rast looked back at the 1519 Leipzig Debate to use Martin Luther’s words for where authority rightly comes from; That, “A simple layman armed with Scripture is to be believed above a pope or a council without it.”

“And, I would add,” Dr. Rast immediately appended, “a pastor or a deaconess.”

Two years later, in April of 1521, Luther would give his famous Here-I-Stand speech at the Imperial Diet in Worms, again on the issue of authority. “Since your most serene majesty and your high mightinesses require of me a simple, clear and direct answer, I will give one, and it is this: I cannot submit my faith either to the pope or to the council, because it is as clear as noonday that they have fallen into error and even into glaring inconsistency with themselves. If, then, I am not convinced by proof from Holy Scripture, or by cogent reasons, if I am not satisfied by the very text I have cited, and if my judgment is not in this way brought into subjection to God’s word, I neither can nor will retract anything; for it cannot be either safe or honest for a Christian to speak against his conscience. Here I stand; I cannot do otherwise; God help me! Amen.”

“Ask yourself,” Dr. Rast went on, speaking of times when leadership and authority is called into question in a ministerial or service setting: “what’s at stake? Me? Or the Word of God? So be very wise.”

He ended on the Word, and the promises given to us in Jesus Christ; those same promises of mercy, grace, and peace carried by pastors and deaconesses into the world. “God works in and through us, in all the seasons of our lives,” Dr. Rast said. “That’s leadership – to understand your place, your gifts, and the gifts He has given to others. And through it all the Lord’s promise remains true: ‘I am with you always, to the end of the age.’”

After the half-hour talk (only shallowly summarized here), the students got together with their faculty mentors over lunch to discuss the topic of leadership and authority further in light of their unique roles as future pastors and deaconesses.

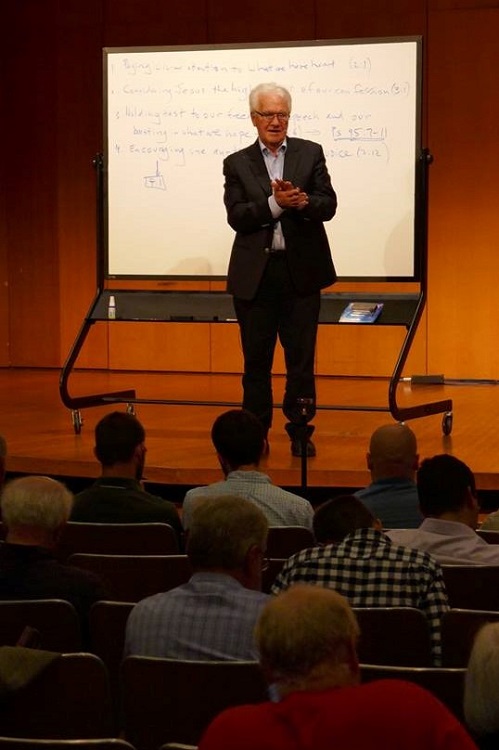

President Rast presented at the International Lutheran Council (ILC) World Conference today in Antwerp, Belgium. This morning the ILC welcomed seventeen new church bodies into membership, ten from Africa, three from Europe, and four from Asia, bringing the total number of church bodies in the ILC to 54, now representing 7.15 million Lutherans.

President Rast presented at the International Lutheran Council (ILC) World Conference today in Antwerp, Belgium. This morning the ILC welcomed seventeen new church bodies into membership, ten from Africa, three from Europe, and four from Asia, bringing the total number of church bodies in the ILC to 54, now representing 7.15 million Lutherans.

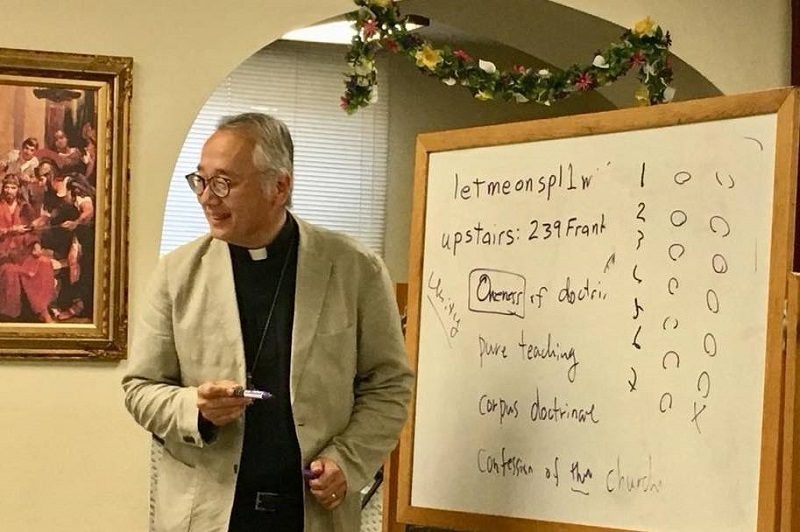

Dr. Masaki led one of the last continuing education courses of the summer nearly three weeks ago, teaching on the Formula of Concord to a little over 20 participants at St. Paul’s Evangelical Lutheran Church in Council Bluffs, Iowa. “As always, so enjoyable to teach the Book of Concord, this time the Formula,” he said of the class.

Dr. Masaki led one of the last continuing education courses of the summer nearly three weeks ago, teaching on the Formula of Concord to a little over 20 participants at St. Paul’s Evangelical Lutheran Church in Council Bluffs, Iowa. “As always, so enjoyable to teach the Book of Concord, this time the Formula,” he said of the class.

Attendees will take a look at the early Christian Church, from the words of the apostles to such examples as Clement of Alexandria, a Gr

Attendees will take a look at the early Christian Church, from the words of the apostles to such examples as Clement of Alexandria, a Gr