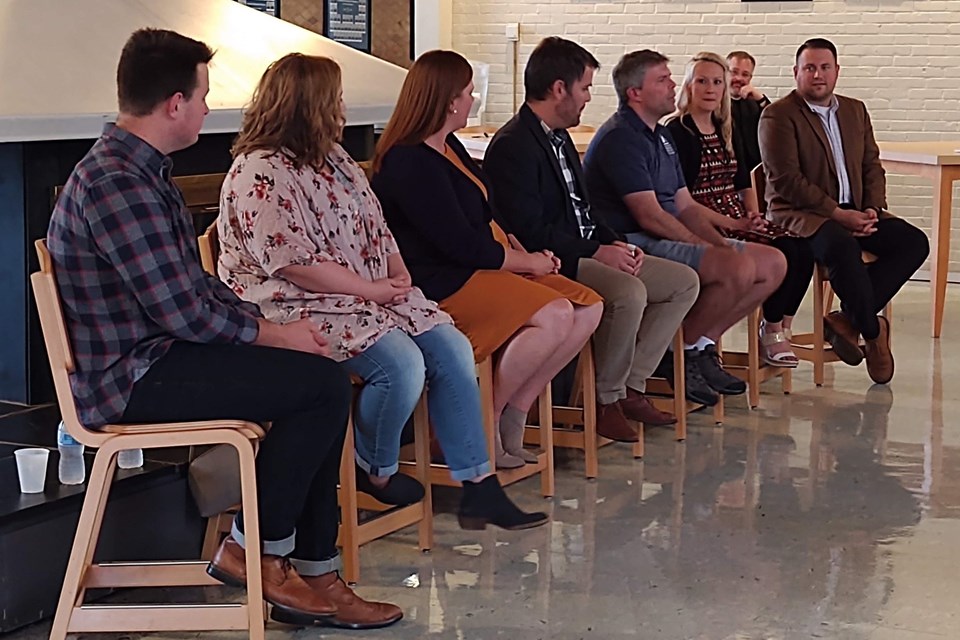

Good Shepherd Institute (GSI) drew to a close yesterday, though a few of the attendees stayed behind for a hymn writing workshop that took place in the afternoon following the official end of the conference. If you’ve been keeping an eye on the CTSFW Facebook page for the past couple of days, you’ll have noted the extra choral services as well as the special music featured in daily chapel on Monday and Tuesday. GSI is a learning conference with very strong ties to music; participants include pastors, church musicians, worship planners, and laypeople with a love for the hymnody of the Church.

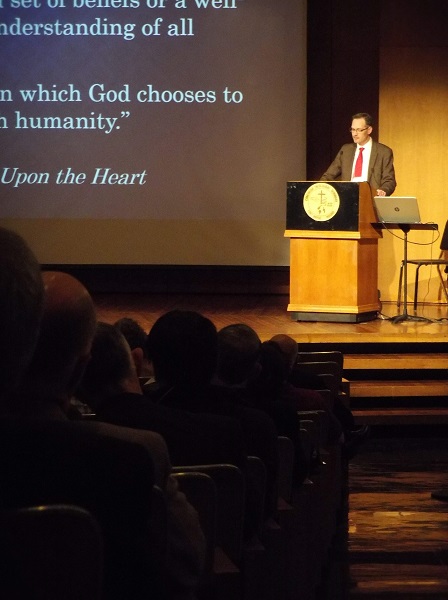

This year’s conference was focused on the music of the Church as both a living tradition and something new, with the first main presentation on Monday morning focused on Heinrich Schütz, as this year is the 400th anniversary of his Psalms of David. Dr. Daniel Zager of the Eastman School of Music presented on Schütz’s psalm settings, with the Concordia Lutheran High School Chamber Choir singing samples of his setting for Psalm 98 to demonstrate the techniques used to capture the text-rich psalm.

Schütz lived from 1585-1672, and wrote music for multiple choirs to sing (you’ll notice in this presentation there are essentially two choirs singing back and forth, interweaving and echoing one another) as well as smaller pieces of sacred music, written when the church was struggling and he had only a few musicians at hand to sing or play. His settings were intended to help listeners understand the text, without the music sounding either perfunctory or overly long. For example, you can hear in parts where the voices themselves are used to indicate sounds, like the trumpets referred to in the text and the sound of rushing water with notes cascading down.

In this clip, Dr. Zager is explaining some of the musical techniques at work in verse 4 of Psalm 98. It’s hard to hear exactly what he’s saying, but essentially he’s explaining how Schütz used two full-part choirs to go back and forth, essentially imitating the text repetition as well as to capture the feeling of shouting for joy referred to in the text. You’ll notice that about half of the Concordia Chamber Choir is sitting in the audience, as they were unable to all fit on stage, with some singing along and others taking a break. The full choir sang the entire Psalm 98 setting in chapel less than an hour later, which you can watch here:

“Never have I presented a paper with singers present,” Dr. Zager said at the end of his presentation, as the choir filed out to prepare for chapel. “This is extraordinary.” He also answered a few questions at the end, one of which was from a church musician wondering if it would be possible to adapt the music as needed to different settings; for example, she wondered if she could have a small choir sing one of the choir parts and replace another with a brass part. Dr. Zager’s response: absolutely. This music was designed to be flexible, able to be tailored to any church setting. It’s one of the great blessings of Schütz’s work.

After chapel, Dr. Samuel Eatherton, a minister of music at Zion Lutheran Church and School in Dallas, Texas, where he teaches music to 3rd–8th graders, spoke on “Church Music for Children”; specifically, how hymns and liturgy form children spiritually. Music helps people connect emotionally with the truth of God’s Word and a child’s faith often develops through music. In fact, neuroscience has found that music binds movement, thoughts, emotions, and memory together in the brain. Regular patterns of bodily rituals ingrain neural pathways.

After chapel, Dr. Samuel Eatherton, a minister of music at Zion Lutheran Church and School in Dallas, Texas, where he teaches music to 3rd–8th graders, spoke on “Church Music for Children”; specifically, how hymns and liturgy form children spiritually. Music helps people connect emotionally with the truth of God’s Word and a child’s faith often develops through music. In fact, neuroscience has found that music binds movement, thoughts, emotions, and memory together in the brain. Regular patterns of bodily rituals ingrain neural pathways.

Children will be formed, whether you will it or not. So we ask ourselves: how are they formed? Liturgy is an excellent tool in the church. Children sing before they learn how to read, and music itself assists with memory (think of the many knowledge songs you learned and still know from elementary school). Liturgy’s predictable elements and repetition help children to internalize information. Though they may not understand all the words they sing, singing helps them carry these concepts in their mind until they are old enough to understand. This is the power of tacit knowledge: knowledge experienced by a child becomes a part of that child.

Monday afternoon then gave participants eight sectionals to choose from, with time for each person to attend three. Sectionals tend to fall on two lines: informational and practical. The library offered tours of the new art exhibit on display (“With Angels and Archangels”) and later participants had the opportunity to attend a class with Dr. Charles Gieschen leading a biblical study of the angels. Rev. Stephen Starke of St. John Lutheran Church Amelith in Bay City, Michigan, presented on another musician’s anniversary (Jaroslav Vajda, a fellow pastor and hymn writer born 100 years ago). Professor Robert Rhein of Bethel University, Mishawaka, Indiana, spoke on faithful hymn translation while his wife, Sandra Rhein, a hymnal consultant for LCMS international missions, held a class directly above him in the second floor of Wyneken Hall on the three new Lutheran hymnals recently published in Kenya, China, and Ethiopia.

Though not a hymn translator, Prof. Rhein translates opera pieces from Italian into English, and has experience preserving a text’s original meaning while making sure it still fits rhyme and meter. In music translation, you rarely (if ever) can use formal equivalence translation, which means word-for-word translation, and instead generally operate on dynamic equivalence, meaning translation that captures the original meaning and feel, though the words may not be an exact translation.

Though not a hymn translator, Prof. Rhein translates opera pieces from Italian into English, and has experience preserving a text’s original meaning while making sure it still fits rhyme and meter. In music translation, you rarely (if ever) can use formal equivalence translation, which means word-for-word translation, and instead generally operate on dynamic equivalence, meaning translation that captures the original meaning and feel, though the words may not be an exact translation.

In the Missouri Synod, we prioritize the stricter formal equivalence for biblical translation. Hymns, however, are an appropriate place for the dynamic style, as it is necessary to retain the poetic nature of the form. Words don’t necessarily exist across languages, or sometimes they do but they don’t fit the rhyme or meter scheme. Take, for example, the solas: Sola Scriptura, Sola Fide, and Sola Gratia. Grace is easy to rhyme, but what about “Scripture” or even “faith”? Thus “Word” is a popular replacement. You can also try inverting the word order. There are also opposing strengths and weaknesses in different language. English uses powerful and simple monosyllabic phrases, which is rare in most European languages. On the other hand, English also has highly variable stress patterns, which is difficult for poetry since a good rhyme rhymes on the stressed syllable. Italian and Spanish don’t have many monosyllables, but everything rhymes easily within the language; we pray, we eat, we sing all rhyme in Italian and Spanish.

Up the stairs from her husband, Mrs. Rhein was speaking on the international hymnal projects. These countries desire a stronger Lutheran identity, and when they see the treasures that hymnals hold, they desire it for themselves. In Africa, Pentecostalism has swept into the country bringing with it its soloist-style, damaging both doctrine and congregational singing. Interestingly, the grass roots movement demanding stronger hymnals comes from their young people. “They were tired of the overpowering volume of Pentecostal style singing,” she explained.

Up the stairs from her husband, Mrs. Rhein was speaking on the international hymnal projects. These countries desire a stronger Lutheran identity, and when they see the treasures that hymnals hold, they desire it for themselves. In Africa, Pentecostalism has swept into the country bringing with it its soloist-style, damaging both doctrine and congregational singing. Interestingly, the grass roots movement demanding stronger hymnals comes from their young people. “They were tired of the overpowering volume of Pentecostal style singing,” she explained.

When the LCMS Office of International Mission (OIM) commits to a hymnal project, they appoint a committee; Mrs. Rhein serves that committee as an advisor and a liaison between them and the OIM. She has found that generally most of the work from these committees ends up with one or two people—those who have the most passion, skill, and vision. Usually pastors but sometimes church musicians. These projects are driven by the people in their home countries.

The other four sectionals were more practical in nature. Mark Knickelbein is an editor of Music/Worship at CPH (as well as composer and church musician), so he led a class on the Lutheran Service Builder and how to use this internet-based software as a tool to encourage hymnal use in congregations. Associate Kantor of CTSFW, Matt Machemer, led a class in the balcony of Kramer Chapel, sight-reading several Lent and Easter choral pieces with the church musicians and worship planners in attendance. This was the first class that primarily featured singing, but not the only one in which the audience broke out into song: the audience sang at least one hymn stanza in nearly every presentation. GSI participants tend to be musically trained, either through profession or simply through church attendance, and more than eager to accommodate a request from any presenter who asks for a congregational demonstration of a piece.

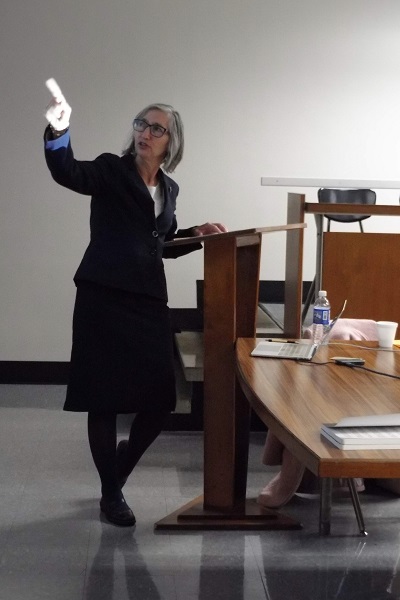

CTSFW Kantor Kevin Hildebrand also presented a sectional on singing, though his was focused in a more general sense on characteristics of good hymn tunes—essentially, what makes a tune easy for a congregation to pick up. Finally, Katie Schuermann, the soprano soloist featured at the choral vespers service the night before, who studied vocal pedagogy and earned a graduate degree in Choral Conducting, held a class on vocal health for amateur singers. She taught her class from the perspective of a conductor, stressing the importance of not only the voice but the whole body as a tool for singing. Dancers practice in front of mirrors, she pointed out, but who is the mirror for the singer? “The conductor,” she answered. “They’re likely going to use you as a model. Model the posture and expressions you want.” Conducting is a role that demands patience; successful conducting is communication between conductor and singers. “We discipline ourselves and teach our singers,” she explained.

CTSFW Kantor Kevin Hildebrand also presented a sectional on singing, though his was focused in a more general sense on characteristics of good hymn tunes—essentially, what makes a tune easy for a congregation to pick up. Finally, Katie Schuermann, the soprano soloist featured at the choral vespers service the night before, who studied vocal pedagogy and earned a graduate degree in Choral Conducting, held a class on vocal health for amateur singers. She taught her class from the perspective of a conductor, stressing the importance of not only the voice but the whole body as a tool for singing. Dancers practice in front of mirrors, she pointed out, but who is the mirror for the singer? “The conductor,” she answered. “They’re likely going to use you as a model. Model the posture and expressions you want.” Conducting is a role that demands patience; successful conducting is communication between conductor and singers. “We discipline ourselves and teach our singers,” she explained.

Some basic tips included teaching singers where tension belongs—not in the shoulders, arms, or hands where they naturally want to hold it (singing is a very vulnerable act, so the tension is an act of protection), but in the abdomen and stomach. She doesn’t worry about the diaphragm, but focuses rather on the intercostal muscles around the ribs. Warmups are about making sure the body is active and ready, for singing is the act of breathing, supporting, and projecting and takes the whole body’s participation. She had the whole class go through practice exercises and stretches. It’s very hard to sing incorrectly when you have correct posture.

She also took a few minutes to talk about the aging voice. “As we age, something called presbyphonia happens,” she said. “What happens is collagen sets in the vocal folds. You can imagine what that does. You want those vocal folds to be moist and loose and agile, right? When collagen sets in the vocal folds it stiffens them. And that’s part of what you’re experiencing when that tone just is not as vibrant as it used to be, you’re not able to make as smooth of a sound. It’s not your fault, it’s just part of aging, okay? Another thing that happens with presbyphonia, the surrounding elastin fibers, you know that are around your vocal folds, those atrophy. They decay. Isn’t that terrible? I’m sorry. But our life in Christ is eternal; there are songs for us to sing in heaven.”

“It’s all normal but frustrating, I know,” she added. “You are just going to reach times where your voice just doesn’t do what it used to, but that doesn’t mean you stop singing. There is beauty in that change and sound as well.”

Two final main presentations finished up GSI the next day: Dr. Paul Grime, CTSFW Dean of the Chapel, on “An Embarrassment of Riches: Choosing What to Sing,” and Prof. Joseph Herl of Concordia University, Nebraska, and Peter Reske, Senior Editor of Music/Worship at CPH, spoke jointly on the LSB Companion to the Hymns, set to be released this December 5.

“We should know nothing to sing or say, save Jesus Christ our Savior,” Martin Luther wrote in a preface to the Wittenberg Hymnal in 1524. Dr. Grime pointed out that, while some of the later reformers like Calvin limited church music to that provided by the Bible (meaning the psalm hymns), Luther translated Latin hymns into German, improved medieval German hymns, and wrote his own. Though he only wrote about three dozen hymns, by not limiting church music to the psalms, he opened up the church to new music by hymn writers for centuries.

The breadth and depth of our hymnal reflects that. We have hymns from many continents and ages, from Europe to Africa and from the past age to the present. We don’t stop writing hymns or books of theology just because excellent hymns and books have already been written. “The Spirit continues to give gifts to the Church,” Dr. Grime said.

He went on to explain the gift of a wide variety of hymns: like the love languages (that each of us has a specific way in which we show and receive love), Dr. Grime suggests that people also have different faith languages. The analogy isn’t perfect and shouldn’t be taken too far, he added, but you can see this play out in our different dispositions and tastes. Matter-of-fact vs. poetic; complex vs. simple; cerebral vs. emotive. For example, LSB 655 “Lord Keep Us Steadfast in Your Word” is a textually dense hymn written by Martin Luther whereas LSB 543 “What Wondrous Love Is This” is a far more modern and repetitious piece: yet both are theologically sound, centered on what Christ has done for us. You need not pit these against each other, but instead recognize that they will appeal to different people, perhaps even in the same congregation.

The most important consideration when choosing hymns: the people who are doing the singing. And by drawing hymns from across countries, ages, and eras, you serve your whole congregation. “And,” he added, “you may learn something not natural to your faith language.”

As to the less theologically-meaty or even sound hymns, Dr. Grime suggests that you slowly introduce stronger hymns as substitutes. This is not a fast process; it can take five, ten, fifty years. When you serve a congregation, you take every member’s past and experiences into consideration. You are also not called to be pressured by other churches or congregations and what they do. “You serve your people,” he said. In every case, we trust God to bless the proclamation of the Gospel through the church’s singing.

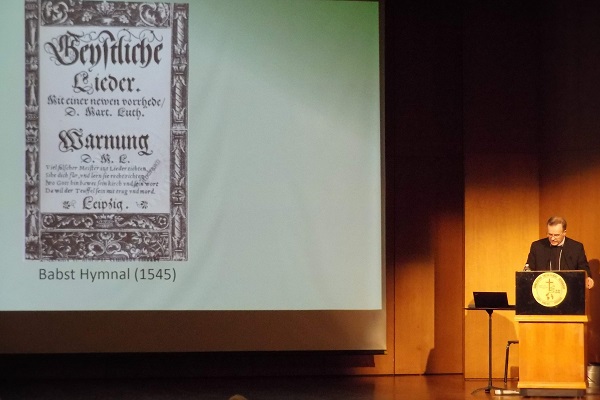

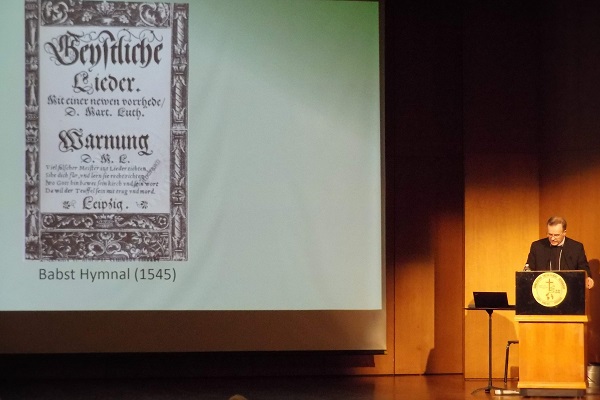

Finally, Professor Herl opened the last presentation with the almost-published LSB Companion to the Hymns. It’s a 2,000+ page scholarly piece written with the assistance of 150 authors (about 10 of whom were in the audience), in which CPH went back to the primary sources for every hymn to better track who wrote the text, tune, and setting, and to track biographical information, historical contexts, and the Scripture upon which each hymn was originally based. Because of the work done for the Companion, CPH made over 500 changes to the attributions in the LSB.

“My favorite part is the index,” Prof. Herl said, then, to laughter: “Actually, I’m serious.” They indexed each hymn according to an enormous number of attributes; i.e. which of the European Lutheran hymns were written by pietists? Was this Anglican hymn writer an Anglo-Catholic or only slightly Anglican? What was going on the world politically and theologically at the time this hymn was created?

Why do this? Because it tells you the original intention of the author. For example, LSB 663 (“Rise, My Soul, to Watch and Pray”) is about watching lest you fall into sin; lo and behold: written by a pietist, a religious movement in which adherents strive for a sinless life as proof of their faith. The emphasis of the hymn is on Christian obedience. Christian obedience is not a bad subject for a hymn, but its pietistic origin is a reminder that you must remember the Christian in the congregation struggling and failing to live a sinless life. There is no Gospel promise here to comfort him. So what do you do? Sing the hymn, and then follow it up later in the service with another: LSB 594 “God’s Own Child, I Gladly Say It.” Here is comfort: it points the struggling Christian to his baptism. “Both hymns are useful in pastoral care,” Prof Herl said, “but in differing circumstances.”

Mr. Reske then took a turn to talk about what wasn’t in the LSB Companion. While their research was thorough, there is still much lost to time. He told stories of the information they could find, the circuitous routes through which they could find some information but never found others, and explained that of the 104 still-living hymn writers who have attributions in the LSB, CPH heard back from 95 of them to confirm the facts presented in their biographies. By researching each hymns origins, you can find original sources and stories.

The 95th still-living hymn writer contacted CPH this summer. Bernard Kyamanywa was born in 1938 and wrote the Tanzanian hymn “Christ Has Arisen, Alleluia” (LSB 466) in the 1960s. Currently in the LSB, the music is simply attributed as “Tanzanian.” They can now update that: his son took a video of Rev. Kyamanywa singing the hymn he wrote, and he was able to confirm that he was not only the author of the text but the composer of the tune as well. It was one of many stories told that day.

GSI closed with the Litany for Travelers: ending with a service of prayer for safe travels, God’s blessings on the participants, and, of course, with singing.

To learn more about GSI (or to register for next year if you already know you’d like to come), go to www.ctsfw.edu/GSI. Email Music@ctsfw.edu for any questions.

After chapel, Dr. Samuel Eatherton, a minister of music at Zion Lutheran Church and School in Dallas, Texas, where he teaches music to 3rd–8th graders, spoke on “Church Music for Children”; specifically, how hymns and liturgy form children spiritually. Music helps people connect emotionally with the truth of God’s Word and a child’s faith often develops through music. In fact, neuroscience has found that music binds movement, thoughts, emotions, and memory together in the brain. Regular patterns of bodily rituals ingrain neural pathways.

After chapel, Dr. Samuel Eatherton, a minister of music at Zion Lutheran Church and School in Dallas, Texas, where he teaches music to 3rd–8th graders, spoke on “Church Music for Children”; specifically, how hymns and liturgy form children spiritually. Music helps people connect emotionally with the truth of God’s Word and a child’s faith often develops through music. In fact, neuroscience has found that music binds movement, thoughts, emotions, and memory together in the brain. Regular patterns of bodily rituals ingrain neural pathways. Though not a hymn translator, Prof. Rhein translates opera pieces from Italian into English, and has experience preserving a text’s original meaning while making sure it still fits rhyme and meter. In music translation, you rarely (if ever) can use formal equivalence translation, which means word-for-word translation, and instead generally operate on dynamic equivalence, meaning translation that captures the original meaning and feel, though the words may not be an exact translation.

Though not a hymn translator, Prof. Rhein translates opera pieces from Italian into English, and has experience preserving a text’s original meaning while making sure it still fits rhyme and meter. In music translation, you rarely (if ever) can use formal equivalence translation, which means word-for-word translation, and instead generally operate on dynamic equivalence, meaning translation that captures the original meaning and feel, though the words may not be an exact translation. Up the stairs from her husband, Mrs. Rhein was speaking on the international hymnal projects. These countries desire a stronger Lutheran identity, and when they see the treasures that hymnals hold, they desire it for themselves. In Africa, Pentecostalism has swept into the country bringing with it its soloist-style, damaging both doctrine and congregational singing. Interestingly, the grass roots movement demanding stronger hymnals comes from their young people. “They were tired of the overpowering volume of Pentecostal style singing,” she explained.

Up the stairs from her husband, Mrs. Rhein was speaking on the international hymnal projects. These countries desire a stronger Lutheran identity, and when they see the treasures that hymnals hold, they desire it for themselves. In Africa, Pentecostalism has swept into the country bringing with it its soloist-style, damaging both doctrine and congregational singing. Interestingly, the grass roots movement demanding stronger hymnals comes from their young people. “They were tired of the overpowering volume of Pentecostal style singing,” she explained. CTSFW Kantor Kevin Hildebrand also presented a sectional on singing, though his was focused in a more general sense on characteristics of good hymn tunes—essentially, what makes a tune easy for a congregation to pick up. Finally, Katie Schuermann, the soprano soloist featured at the choral vespers service the night before, who studied vocal pedagogy and earned a graduate degree in Choral Conducting, held a class on vocal health for amateur singers. She taught her class from the perspective of a conductor, stressing the importance of not only the voice but the whole body as a tool for singing. Dancers practice in front of mirrors, she pointed out, but who is the mirror for the singer? “The conductor,” she answered. “They’re likely going to use you as a model. Model the posture and expressions you want.” Conducting is a role that demands patience; successful conducting is communication between conductor and singers. “We discipline ourselves and teach our singers,” she explained.

CTSFW Kantor Kevin Hildebrand also presented a sectional on singing, though his was focused in a more general sense on characteristics of good hymn tunes—essentially, what makes a tune easy for a congregation to pick up. Finally, Katie Schuermann, the soprano soloist featured at the choral vespers service the night before, who studied vocal pedagogy and earned a graduate degree in Choral Conducting, held a class on vocal health for amateur singers. She taught her class from the perspective of a conductor, stressing the importance of not only the voice but the whole body as a tool for singing. Dancers practice in front of mirrors, she pointed out, but who is the mirror for the singer? “The conductor,” she answered. “They’re likely going to use you as a model. Model the posture and expressions you want.” Conducting is a role that demands patience; successful conducting is communication between conductor and singers. “We discipline ourselves and teach our singers,” she explained.

We had nearly 40 visitors with us this week for Luther Hostel, featuring lectures on Creation and the New Creation. Attendees also had the opportunity to join the campus community, worshipping in Kramer Chapel, drinking coffee and eating meals with the students and faculty, and even attending regular classes at intervals throughout their three-day visit. Special sessions on the theme are set aside in Luther Hall, taught by such faculty as Dr. Gifford Grobien, Dr. David Scaer, Dr. Ryan Tietz, Dr. Benjamin Mayes, Dr. Charles Gieschen, Rev. John Dreyer, Dr. William Weinrich, and Dr. Jeffrey Pulse.

We had nearly 40 visitors with us this week for Luther Hostel, featuring lectures on Creation and the New Creation. Attendees also had the opportunity to join the campus community, worshipping in Kramer Chapel, drinking coffee and eating meals with the students and faculty, and even attending regular classes at intervals throughout their three-day visit. Special sessions on the theme are set aside in Luther Hall, taught by such faculty as Dr. Gifford Grobien, Dr. David Scaer, Dr. Ryan Tietz, Dr. Benjamin Mayes, Dr. Charles Gieschen, Rev. John Dreyer, Dr. William Weinrich, and Dr. Jeffrey Pulse.

Born on June 24, 1925, Dr. Maier II attended Concordia Seminary, St. Louis, where his father served as a professor, and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in Exegesis and Systematics in 1948. A year later, he received a Master of Arts in Classical Languages from Washington University in St. Louis. On September 11, 1949, his father ordained and installed him at Faith Lutheran Church, a rural congregation in Elma, New York, where he met his future bride, Leah M. Gach. They were married in 1951 and had two sons, Walter III and David.

Born on June 24, 1925, Dr. Maier II attended Concordia Seminary, St. Louis, where his father served as a professor, and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in Exegesis and Systematics in 1948. A year later, he received a Master of Arts in Classical Languages from Washington University in St. Louis. On September 11, 1949, his father ordained and installed him at Faith Lutheran Church, a rural congregation in Elma, New York, where he met his future bride, Leah M. Gach. They were married in 1951 and had two sons, Walter III and David. In 1996, while chairing the Seminary’s 150th anniversary committee, Dr. Maier II wrote the following in the January–April Issue of Concordia Theological Quarterly: “From the time the first classes were taught in the parsonage of St. Paul’s Lutheran church in Fort Wayne, in October of 1846, until the present, when the seminary occupies a beautiful campus of two hundred acres near the St. Joseph River, this ‘school of the prophets’ has served as God’s instrument in preparing over four thousand men for the ministerium of The Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod. It has also, through its graduate and extension programs, assisted in the advanced theological education of many pastors through the years. These are great blessings from, and grounds of profound gratitude to, the Lord of the church. These are many reasons for the seminary and the church to rejoice during the current celebratory period.”

In 1996, while chairing the Seminary’s 150th anniversary committee, Dr. Maier II wrote the following in the January–April Issue of Concordia Theological Quarterly: “From the time the first classes were taught in the parsonage of St. Paul’s Lutheran church in Fort Wayne, in October of 1846, until the present, when the seminary occupies a beautiful campus of two hundred acres near the St. Joseph River, this ‘school of the prophets’ has served as God’s instrument in preparing over four thousand men for the ministerium of The Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod. It has also, through its graduate and extension programs, assisted in the advanced theological education of many pastors through the years. These are great blessings from, and grounds of profound gratitude to, the Lord of the church. These are many reasons for the seminary and the church to rejoice during the current celebratory period.”