Dr. John Kleinig, Professor Emeritus at Luther College, Adelaide, South Australia

The triune God is an author. In fact, He is the only true author. The Father is the author of the world He created, and its story. The Son is the author of the Church that He has redeemed, and its story. The Spirit is the author of the Scriptures that He has inspired, and its story.

Yet the word that has been authored by the Spirit is by far the greatest of all these wonders, for the Word of the Spirit discloses the mysteries of creation and redemption. It is the mystery of all mysteries. The Bible, the Scriptures as the word of the spirit. That’s Johann Georg Hamann’s great theme in his London writings.

Hamann was, in fact, not a theologian, but a humble employee in the bureaucracy of the Prussian Empire, which he hated. He was a man of letters—of journalism. He never published the London writings, nor did he intend to publish them. They were for himself; a kind of spiritual journal shared only with his father, brother, and two friends. But these personal writings reveal that he was one of the few theologians of the cross in his day.

Hamann lived from 1730-1788, living most of his life in East Prussia on the southeast corner of the Baltic Sea. Born to parents of modest means, he had a rather conventional Lutheran upbringing, with a father who was still largely orthodox and a mother influenced by Lutheran pietism. He studied theology and then switched over to law. While at his university, he became a fashionable advocate of the Enlightenment with his two best friends. He had a speech impediment that precluded him from becoming a pastor or lawyer, and a haphazard class attendance pattern; he failed to graduate. But by the end of his life, he was considered one of the best read men of his generation.

While on a trade mission to London (to make a secret trade deal, of which we still don’t know many details), he fell into bad company, including a group of homosexuals. He got lost. He got deep into debt because he was a generous person and a soft touch. He suffered ill health from overindulgence and experienced a deep bout of depression from social isolation. He was a gregarious person who felt only comfortable in the company of like minds. A young Christian couple provided him cheap accommodation and he went into conclusion, living on a diet of porridge. “Which did him a world of good, he said.”

He found no consolation in the books he had previously bought, and on impulse he bought himself an English Bible. As he read, he became aware of the veil between his reading and his understanding of the Bible. On Palm Sunday, 1758, it struck him for the first time that God was speaking to him personally as he was reading it. And he switched over: he no longer read it critically, but meditatively, particularly as it critiqued him and his rationalism.

On the day that he began to read the Bible for the second time in a new way (as God speaking to him), he began to write down the results of his meditations in a kind of spiritual journal. Then on a Friday evening in March, he fell into a deep reverie as he was reading Deuteronomy 5: the passage where God spoke to His people face to face, speaking the Decalogue to them on Mount Sinai, that was so terrifying that they asked God to provide Moses as mediator. Here is how he described what happened to him on that evening:

“I recognized my own offenses in the history of the Jewish people. I read the story of my own life, and thanked God for His forbearance with His people. Because nothing but such an example could justify a similar hope for me…I could no longer hide from God that I was the killer of my brother, the murderer of His begotten Son. Despite my weakness, my long resistance I had put up against His witness, the Spirit of God kept on revealing to me still more and more the mystery of divine love and the benefit of faith in our gracious, only Savior.”

In his broken heart he heard how the blood of Jesus, which cried out for vengeance, was also proclaiming God’s grace and love to him. And that Word broke his blind, hard, rocky, stubborn heart, and he surrendered it to God for re-creation by His Holy Spirit.

He was not converted as he was already a Christian, but rather transformed. His meditation from March 19–April 21, 1758, reveal his spiritual awakening and transformation from a rational intellectual to a faithful confessor of the triune God. He meditates on those parts that strike him, that address him personally or challenge him intellectually as a child of the Enlightenment. They identify his blind spots, in order to grant him deeper and more accurate insight into the spiritual realities that they portray.

From April 29–May 6, 1758, he meditated devotionally on six hymns which all consider the hidden glory of Christians who are not only made in God’s image but also participate in the communion of the Son with Father by the Holy spirit.

May 16, 1758: Apart from illumination by the Holy Spirit, both reason and faith are blind. Our knowledge is there limited and partial. Then in undated meditations on Newton’s Study on Prophecies, he observed that the Old Testament does not just record some Messianic prophecies, but that “every biblical story is a prophecy that would be fulfilled through all centuries—and in every human soul.”

The tone throughout his meditations changes. The comments become less abstract and intellectual and become more personal and devotional. By the end, he wrote a biographical look back at his life in light of his new understanding of Scripture.

From an undated piece, “On the Interpretation of Sacred Scripture”:

“Who would, like Paul in 1 Corinthians 1:25, be so bold as to speak of God’s weakness? No one, except the Spirit who searches the depths of the godhead, could have disclosed to us this prophecy, which has, more than ever before, been fulfilled in our own times, the prophecy that not many who are wise according to the flesh, not many who are mighty, not many who are of noble birth, are called to the kingdom of heaven, and that the great God has desired to reveal His wisdom and power by deliberately choosing what is foolish in the world to shame the mighty, choosing what is lowly and despised, yes things that are not, in order to bring to nothing things that are, things that boast of what they are (1 Cor. 1:26-28).”

Or, in the words of 1 Corinthians 1:25-31:

For the foolishness of God is wiser than men, and the weakness of God is stronger than men.

For consider your calling, brothers: not many of you were wise according to worldly standards, not many were powerful, not many were of noble birth. But God chose what is foolish in the world to shame the wise; God chose what is weak in the world to shame the strong; God chose what is low and despised in the world, even things that are not, to bring to nothing things that are, so that no human being might boast in the presence of God. And because of him you are in Christ Jesus, who became to us wisdom from God, righteousness and sanctification and redemption, so that, as it is written, “Let the one who boasts, boast in the Lord.”

Today’s partial summary was taken from both Dr. Kleinig’s lecture as well as his handout that quickly sketches Hamann’s London writings, which he shared with the audience.

The Word creates the faith that is necessary to receive the Gospel. In Luther’s confession of 1528, Luther’s eschatological concepts were both a personal testimony and a true exposition of the faith of all Christendom; what all true Christians believe and Scripture teaches.

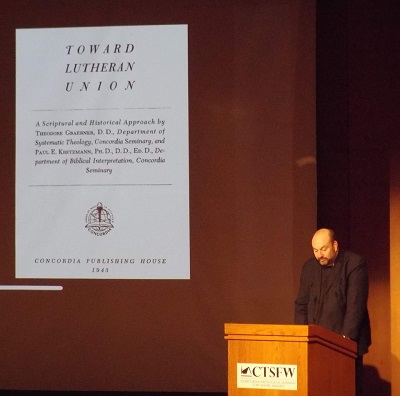

The Word creates the faith that is necessary to receive the Gospel. In Luther’s confession of 1528, Luther’s eschatological concepts were both a personal testimony and a true exposition of the faith of all Christendom; what all true Christians believe and Scripture teaches. The religious scene in 1950 America: America is on the top of the world, everyone has children, and everything is looking up for American religion. The good guys won. The ecumenical movement is in full swing. Billy Graham is a study in American evangelicalism.

The religious scene in 1950 America: America is on the top of the world, everyone has children, and everything is looking up for American religion. The good guys won. The ecumenical movement is in full swing. Billy Graham is a study in American evangelicalism.

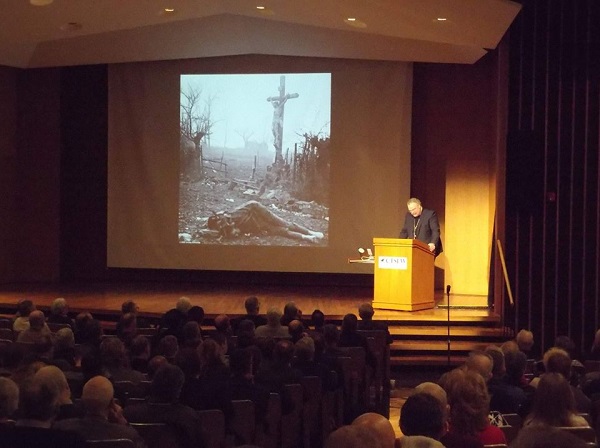

Substitutionary atonement’s importance is obvious throughout the Old Testament and New Testament, as well as to the Church’s theological battles following. Indeed, penal substitutionary atonement comes naturally to Christians. Every biblical doctrine is related to every other doct

Substitutionary atonement’s importance is obvious throughout the Old Testament and New Testament, as well as to the Church’s theological battles following. Indeed, penal substitutionary atonement comes naturally to Christians. Every biblical doctrine is related to every other doct Dr. Arthur Just Jr., CTSFW Professor of Exegetical Theology

Dr. Arthur Just Jr., CTSFW Professor of Exegetical Theology The phrase “penal substitutionary atonement” captures the essence of what I was taught when I was young: that Jesus not only led the perfect life, He also took upon Himself the sins of the world and paid fully for those trespasses with His suffering and death on a cross. In other words, Jesus took o

The phrase “penal substitutionary atonement” captures the essence of what I was taught when I was young: that Jesus not only led the perfect life, He also took upon Himself the sins of the world and paid fully for those trespasses with His suffering and death on a cross. In other words, Jesus took o Dr. John Kleinig, Professor Emeritus at Luther College Adelaide, South Australia

Dr. John Kleinig, Professor Emeritus at Luther College Adelaide, South Australia